A Lasting Ocean Observatory

San Diego, October 7, 2010 -- Agile architecture is essential if a large-scale infrastructure like the Ocean Observatories Initiative is to last three decades, as mandated.

[Note to readers: This article by Miriam Boon first appeared in International Science Grid This Week (iSGTW) and is re-published with iSGTW's permission.]

|

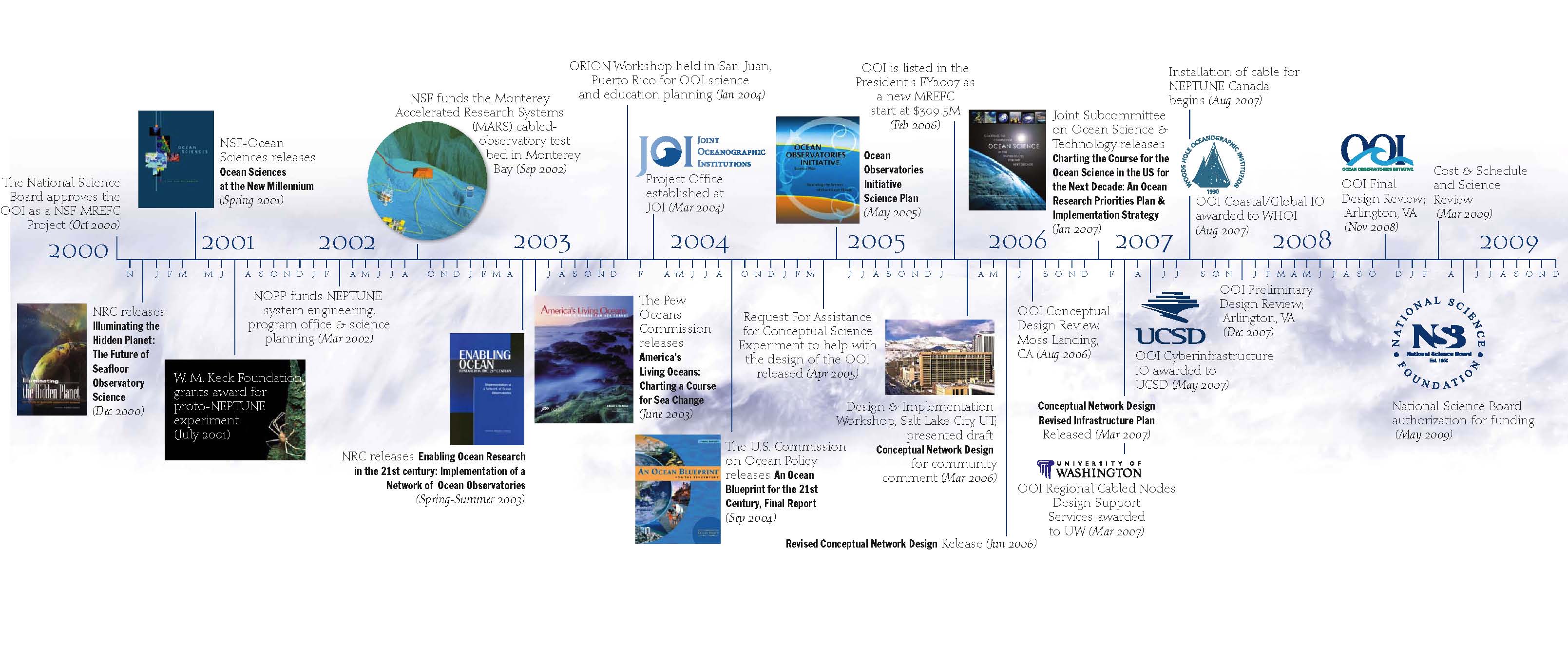

“The Ocean Observatory has been in planning for fifteen years and more,” said Matthew Arrott, OOI’s project manager for cyberinfrastructure [based in the UC San Diego division of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology]. “It is our anticipation, over a 30-year lifespan, that we need to account for user needs and the technology that we are using all changing.”

That’s why they’ve focused their attention on creating an infrastructure that can interface with a wide variety of software packages and computational resource providers.

“The observatory supports a broad range of analysis with the expectation that the majority of the analysis capability will be provided and operated by the user community as opposed to developed and operated by the observatory itself,” Arrott said. “The underlying architecture is designed to support community practices as they are currently defined and executed as well as supporting future uses and practices.”

The OOI will deploy a global network of fixed and mobile real time observation platforms based on a combination of fiber optic and satellite communication technologies for four global, two regional and two coastal arrays. The global platforms are southeast of Greenland, in the Gulf of Alaska, the Argentine Basin and the Southern Ocean off Chile. The coastal arrays will be off the coast of New England and Washington state while the two cabled, regional arrays are located on the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate and off the coast of Oregon.

Once the OOI is up and running, sensors and cameras placed in the oceans around the United States will record and stream live data back to shore. This will include nearly 50 different sensor types recording a variety of chemical, biological, and physical phenomenon, as well as HD video cameras, according to William Pritchett, associate project manager for cyberinfrastructure at the Consortium for Ocean Leadership.

Like many existing ocean observatories, the OOI portal will provide researchers with access to some basic analysis and visualization tools. But OOI’s cyberinfrastructure team expects the serious research to function very differently.

|

“It’s a different world we’re working in. In the old world, everything was about the portal,” Arrott said. “You go to the portal, and you get everything you need.”

Instead, researchers will be able to sign up to receive notifications when new data are available, or set up their own computers to interface directly with a data stream. This makes it possible for researchers to continue using the software packages with which they are already familiar. Even more important is the fact that established, independent software packages such as Matlab will continue to develop as technology evolves, without any additional work on the part of the OOI team.

The OOI approach to computational resources is similarly flexible.

“We have built out a distributed private cloud infrastructure nationally as well as insured that the high bandwidth broadband capabilities are extended into academic and commercial cloud environments so that the community can operate at the scale that they need to without relying on us having the private capacity to manage it, and reach any scale that the community chooses to use,” Arrott explained.

Already, they have plans to interface with Open Science Grid, TeraGrid, and commercial clouds such as Amazon. And of course researchers will be able to use their own local resources, whatever they may be.

Researchers will also be able to control sensors remotely, using a software suite developed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (ASPEN and CASPER) for resource planning and control, and MIT’s Mission Oriented Operating Suite (MOOS) for interfacing with autonomous instrument platforms.

Through OOI, scientists hope to learn more about a variety of topics, including ocean-atmosphere exchange, climate variability, ocean circulation, turbulent mixing, coastal ocean dynamics and ecosystems, fluid-rock interactions, subseafloor biospheres, and plate-scale ocean geodynamics. But these and many other questions will require a worldwide network of ocean observatories, far beyond the scope of OOI.

Instead, OOI will work in tandem with ocean observatories around the world. On a global scale, that means interfacing with the Global Ocean Observing System and the Global Earth Observing System of Systems, as well as the World Meteorological Organization’s Global Telecommunication System. Nationally, they will be working closely with the U.S. Integrated Ocean Observing System and the various ocean observatories affiliated with IOOS. Finally, by interfacing with Neptune Canada, the two observatories will be able to circumscribe the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate, which is one of the Earth’s smallest tectonic plate, located off the coasts of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. These interfaces will come in the form of common object and data models.

When OOI goes live in 2014, it will be the culmination of over fifteen years of planning and five years of construction. In fact, according to Pritchett, it is the largest environmental observatory cyberinfrastructure initiative that has been funded by the National Science Foundation.

Said Pritchett, “The magnitude of the scope, the capabilities this is going to encompass when it’s fully developed, I think it’s going to revolutionize the way ocean science is conducted.”

Related Links