Flexible, Printable Sensors Detect Underwater Hazards

San Diego, July 7, 2011 -- Often breakthroughs in nanoengineering involve building new materials or tiny circuits. But a professor at the University of California, San Diego is proving that he can make materials and circuits so flexible that they can be pulled, pushed and contorted – even under water – and still keep functioning properly.

|

“We have a long-term interest in on-body electrochemical monitoring for medical and security applications,” said Wang, a professor in the Department of NanoEngineering in UC San Diego’s Jacobs School of Engineering. “In the past three years we’ve been working on flexible, printable sensors, and the capabilities of our group made it possible to extend these systems for use underwater.”

Wang notes that some members of his team – including electrical-engineering graduate student Joshua Windmiller – are surfers. Given the group’s continued funding from the U.S. Navy, and its location in La Jolla, it was a logical leap to see if it would be possible to print sensors on neoprene, the synthetic-rubber fabric typically used in wetsuits for divers and surfers.

|

UCSD has a full U.S. patent pending on the technology, and has begun talks on licensing the system to a Fortune 500 company.

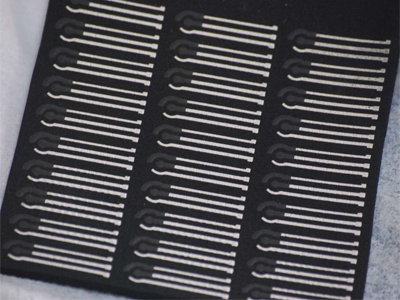

Wang’s 20-person research group is a world leader in the field of printable sensors. But to prove that the sensors printed on neoprene could take a beating and continue working, some of Wang’s colleagues took to the water.

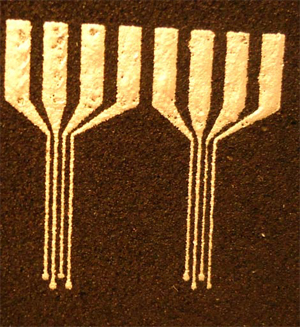

“Anyone trying to take chemical readings under the water will typically have to carry a portable analyzer if they want to detect pollutants,” said Wang, whose group is based in the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology (Calit2) at UCSD. “Instead, we printed a three-electrode sensor directly on the arm of the wetsuit, and inside the neoprene we embedded a 3-volt battery and electronics.”

|

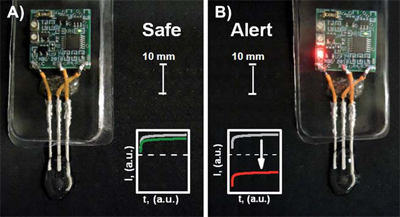

The electronics are packed into a device known as a potentiostat that is barely 19mm by 19mm. (The battery is stored on the reverse side of the circuit board.)

In the experiments described in the Analyst article, Wang and his team tested sensors for three potential hazards: a toxic metal (copper); a common industrial pollutant, phenol; and an explosive (TNT). The device also has the potential to detect multiple hazards. “In the paper we used only one electrode,” noted Wang, “but you can have an array of electrodes, each with its own reagent to detect simultaneously multiple contaminants.”

|

The UCSD team tested the sensor for explosives because of the security hazard highlighted by the 2000 attack on the USS Cole in Yemen. The Navy commonly checks for underwater explosives using a bulky device that a diver must carry underwater to scan the ship’s hull. Using the microsystem developed by Wang and his team, the sensor printed on a wetsuit can quickly and easily alert the diver to nearby explosives.

Wang’s lab has extensive experience printing sensors on flexible fabrics, most recently demonstrating that biosensors printed on the rubber waistband of underwear can be used continuously to monitor the vital signs of soldiers or athletes. The researchers were uncertain, however, about whether bending the printed sensors under water – and in seawater – would still let them continue functioning properly.

|

Wang’s work in flexible sensors grew out of 20 years’ experience with innovations in glucose monitoring, ultimately in the form of flexible glucose strips that now account for a $10 billion market worldwide.

Work on the underwater sensors was supported by the Office of Naval Research.

* Wearable electrochemical sensors for in situ analysis in marine environments, Kerstin Malzahn, Joshua Ray Windmiller, Gabriela Valdés-Ramírez, Michael J. Schöning and Joseph Wang, Analyst, June 2011

Related Links

Joseph Wang Lab

Department of NanoEngineering

Article in Analyst

Article in Chemistry World

Media Contacts

Doug Ramsey, 858-822-5825, dramsey@ucsd.edu