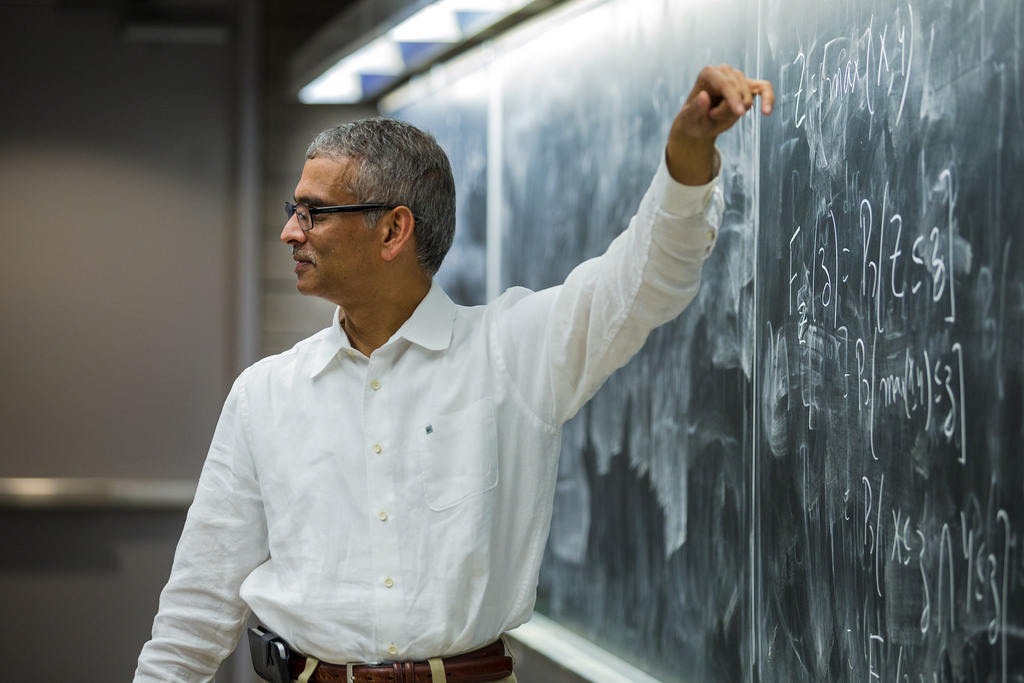

Predicting Uncertainty with Qualcomm Institute Director (and Instructor) Ramesh Rao

Note: In part one of a three-part series, we feature Qualcomm Institute Director Ramesh Rao and his experience teaching Electrical and Computer Engineering 109 — Engineering Probability and Statistics. The series will profile QI personnel who also provide classroom instruction.

San Diego, Calif., March 18, 2014 — Trying to understand uncertainty is part and parcel of Ramesh Rao’s job as director of the Qualcomm Institute, the University of California, San Diego division of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology (Calit2). On any given week, Rao must try to predict the next big trend in research, how the fiscal outlook might change, what the future of academia will look like in five or 10 years.

|

This academic quarter, Rao has also gone back to his roots to look at uncertainty from an engineering perspective. Rao, a professor of electrical engineering, is teaching ECE 109 — a required course for all Jacobs School of Engineering students seeking an undergraduate degree in Electrical and Computer Engineering.

Rao says the course in Engineering Probability and Statistics is crucial for understanding nearly every engineering system, and that’s because nearly every engineering system is compromised by unpredictable phenomena.

“The reason why this course is important to the curriculum is also the reason why it’s important generally: When you design any engineering system today you are almost always confronting limits created by random events like ‘noise,’” explains Rao. Noise is a random fluctuation or disturbance to a signal that can adversely affect communication of that signal.

“Radio wave signals, atmospheric noise, interference — everything from your vacuum cleaner to automobile spark plugs — they all generate noise,” he continues. “When a heart rate monitor is worn around the chest, for example, the monitor reads the electrical signal from your heart and renders the signal as waveform. If you want to integrate such a system into device worn on the wrist like a watch, the signal that reaches the watch becomes fainter and fainter because things like the body’s movement, breathing and static electricity will affect the signal transmission.”

ECE 109 is a math-based foundations course that helps students learn how to how to discriminate between signals and noise and how to cope when noise compromises a signal.

“There is another angle to it,” Rao adds. “We spend so much time in school learning calculus, where the signals or curves are measured by their lengths and slopes In this course, instead of lengths we use probability to measure things by the likelihood of its appearance.

“It’s a bit like re-learning calculus. If you understand the subject matter and make the right connections, everything one learns in calculus comes into play here.”

Rao notes that because the class is considered a ‘fundamental’ course, the emphasis is on mastering techiques, or what he calls “grunt work.”

“There are courses where you see the real life applications and there are courses where you prepare for it,” he says. “This is a grunt work course that will prepare students to have a lot of fun later.”

|

Still, Rao says he is having “the time of my life” teaching ECE 109, and one of the chief reasons he’s so engaged with the 78 students in the course is because he decided to teach “the old-fashioned way.”

“I had gone in with a technology bias,” he says, “having found some online material I could use to supplement the class and thinking that it would have some components of a MOOC.” MOOC stands for Massively Open Online Course, which typically features online lectures and discussions.

“But the actual classroom experience reinforced the value of interactive feedback from my students, and it showed me that the online platform is really the modern evolution of the book, not the modern evolution of the instructor. In person, when the students are really engaged, I can read their faces, and when they’re baffled, I can see that happening in real time. I can coax them interactively into coughing up whatever they are wrestling with in their minds.”

Seokheon “Justin” Cho, Rao’s teaching assistant, has been a TA in several courses and says that “unlike other courses, most of students (in Rao’s class) are very cooperative and enthusiastic about what they study this course. They ask lots of questions, provide interactive feedback, and so on. In addition, it is a rare situation that only few students have dropped this course."

Cho also notes that two holidays this quarter fell on Mondays, one of the days Rao's course is taught. “In general, an instructor doesn't give any make-up classes because of holidays,” he notes, “Prof. Rao, however, has given three make-up classes, even on a Saturday. I think his passion for teaching leads his students to a great zest for studying."

Adds Rao: “I also appreciate students that just hang out with their professor during office hours, even when they don’t have a question. These are important aspects of face-to-face interctions. This is partly how they learn.”

That experience explains, in part, why Rao encourages the staff researchers in the Qualcomm Institute to "take advantage of opportunities to get into the classroom and teach at either the undergraduate or graduate level."

Related Links

Media Contacts

Tiffany Fox, (858) 246-0353, tfox@ucsd.edu