Researchers Demonstrate New Way to Plug "Leaky" Light Cavities

San Diego, Dec. 10, 2014 — Engineers at the University of California, San Diego have demonstrated a new and more efficient way to trap light, using a phenomenon called bound states in the continuum (BIC) that was first proposed in the early days of quantum wave mechanics.

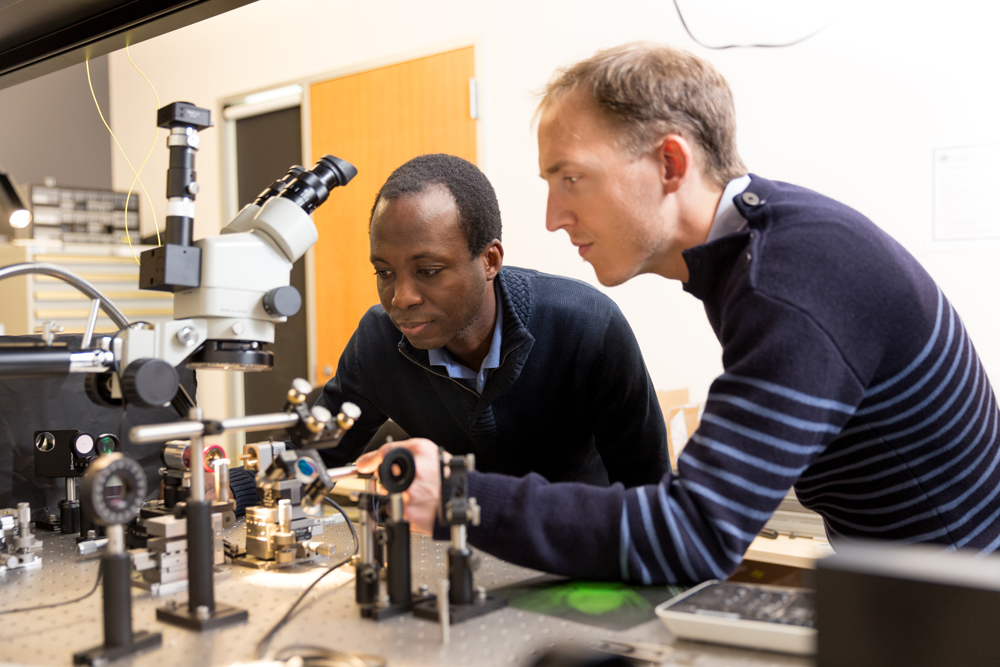

Boubacar Kanté, an assistant professor in electrical and computer engineering at UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering, and his postdoctoral researcher Thomas Lepetit described their BIC experiment online in the rapid communication section of journal Physical Review B. The study directly addresses one of the major challenges currently facing nanophotonics, as researchers look for ways to trap and use light for optical computing circuits and other devices such as tiny switches.

“The goal in the future is to make a computer that performs all kinds of operations using light, not electronics, because electronic circuits are relatively slow. We expect that an optical computer would be faster by three to four orders of magnitude.” Kanté said. “But to do this, we have to be able to stop light and store it in some kind of cavity for an extensive amount of time.”

This research is funded in part by a grant from the Qualcomm Institute at the University of California, San Diego via the institute’s Calit2 Strategic Research Opportunities (CSRO) program to Kante’s project, “Multipolar Optical Materials via Active Fano Resonances.”

To slow down and eventually localize light, researchers rely on cavities that trap light in the same way that sound is trapped in a cave. Waves continuously bounce off the walls of the cavity and only manage to escape after finding the narrow passage out. However, most current cavities are quite leaky, and have not one but multiple ways out. A cavity’s capacity to retain light is measured by the quality factor Q—the higher the Q, the less leaky the cavity.

Lepetit and Kanté sought a way around the leak problem by designing a metamaterials BIC device consisting of a rectangular metal waveguide and ceramic light scatterer. Instead of limiting the size and number of passages where light can escape the cavity, the cavity’s design produces destructive interferences for the light waves. Light is allowed to escape, but the multiple waves that do so through the different passages end up cancelling each other.

“In a nutshell, BICs can enhance your high-Q,” the researchers joked.

Other researchers have worked on ways to trap light with BIC, but the cavities have been constructed out of things like photonic crystals, which are relatively large and designed to scale to the same wavelength as light. The device tested by the UC San Diego researchers marks the first time BIC has been observed in metamaterials, and contains even smaller cavities, Kanté said.

The difference is important, he explains, “because if you want to make compact photonic devices in the future, you need to be able to store light in this subwavelength system.”

Moreover, earlier researchers had reported observing only one BIC within their systems. Lepetit and Kanté observed multiple bound states in their system, which make the light trap more robust and less vulnerable to outside disruptions.

The researchers say trapping light via BIC will likely have a variety of other applications beyond circuitry and data storage. Since the system can hold light for an extended time, it may enhance certain nonlinear interactions between light and matter. These types of interactions can be important in applications such as biosensors that screen small molecules, or compact solar cells.

The publication is “Controlling multipolar radiation with symmetries for electromagnetic bound states in the continuum,” published December 1 in the Rapid Communications section of Physical Review B.

Related Links

Boubacar Kante

Physical Review B Publication

Calit2 Strategic Research Opportunities Program