New CISA3 Special Projects Coordinator: Transforming Students From Consumers into Makers

San Diego, Calif., April 27, 2015 — One might say Dominique Rissolo’s specialty is digging things up – be they artifacts, research funds or human potential.

As a lifelong archaeologist with a fascination for the sea, Rissolo has explored the Yucatan’s coastal sites and caves in search of Maya antiquities related to seafaring, commerce and ritual practice, as well as evidence of the strategies the Maya developed to thrive.

Now, as the newly hired Special Projects Coordinator for the Center of Interdisciplinary Science for Art, Architecture and Archaeology (CISA3) at the University of California, San Diego, Rissolo has embarked on a new search for funding and collaborations that will ensure the Center’s many cultural heritage projects not just survive, but thrive.

Rissolo’s research background makes him especially suitable for the job. Before coming to UC San Diego’s Qualcomm Institute – the home of CISA3 – he earned his PhD in anthropology from UC Riverside and then spent eight years at the Waitt Foundation and National Geographic co-designing and co-managing a grants program that supported a broad range of field-based disciplines as well as developing science communications. Rissolo also has years of experience coordinating expeditions and managing other aspects of field-work, and spent four years teaching anthropology at San Diego State University, where he says he developed a passion for teaching and mentoring.

“I’ve been working with students in the field,” he says, “ever since I started going to field.”

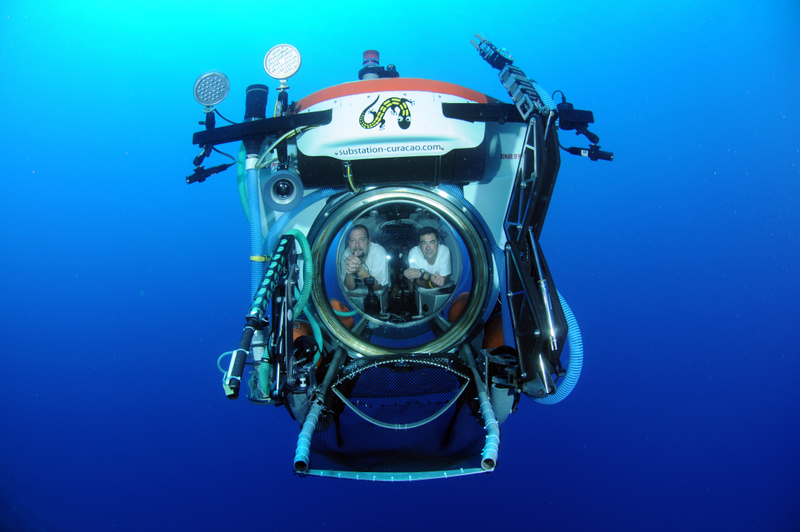

While at Waitt, Rissolo was also involved in a marine robotics program with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to develop autonomous and remotely operated vehicle systems capable of doing deep-water archaeological surveys – something that also happens to be a primary research focus for CISA3.

“One of the more challenging frontiers for cultural heritage diagnostics is submerged cultural heritage,” says Rissolo, who developed an interest in the sea as a child while growing up landlocked in Georgia (“nowhere near the coast, but fantasizing that every pond, swamp, creek and river was some amazing frontier to explore”).

“We have terrestrial and aerial documentation systems pretty well underway,” he continues “and a number of students, like Michael Bianco, Perry Naughton and Antonella Wilby, are working on underwater tools and techniques, but these students are engineers and computer scientists, not necessarily archaeologists." Bianco, for example, is a Ph.D. student at the UC San Diego Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Naughton is a Ph.D. student in the university's Electrical and Computer Engineering program and Wilby is a graduating senior in Computer Science and Engineering (CSE).

"By bringing everyone together, the archaeologists can articulate those most pressing challenges to the individuals who have the skills, creativity and knowledge to meet those challenges and develop solutions.”

As their work progresses, Rissolo says the CISA3 researchers are finding that “a lot of off-the-shelf tools really aren’t appropriate for scientific field research, which speaks to the expertise of our students and the unique contributions to cultural heritage research that are possible through computer science and engineering.

"Another big challenge," he continues, "is the integration of sensors with the aerial or underwater platforms. This is not just about creating pretty visualizations of objects and sites, but collecting data – in a variety of modes – that have real diagnostic and analytical value.”

Underwater systems, Rissolo notes, must be particularly robust. “If it gets wet and goes deep,” he says, “you’re eventually going to lose it. In the world of underwater systems,’two is one and one is none’ because the failure rate is so high and the loss rate is so high. A big part of what we must do is try not to lose the vehicles, which means they need navigation systems that allow us to control the vehicles remotely.”

The problem, says Rissolo, is that the overwhelming number of systems out there, drone wise, are built for hobbyists.

“Our students are really focused on developing the kinds of systems that are designed for scientists,” he continues. “I am working with Michael Hess (a Ph.D. in structural engineering), Dominique Meyer (an undergraduate in physics), and Eric Lo (a CISA3 engineer) on multi-modal aerial survey and mapping in Mexico , for example. There are always challenges with stabilization and automation, as well as aerial prospecting and remote sensing, more accurate site recording and the extent to which we can use these vehicles for site discovery. We want to identify the priorities of the scientific community in terms of data capture and build solutions.

“At the same time,” adds Rissolo, “we don’t want to recreate what folks in the oil and gas industry are doing, which is building and using massive systems that are too costly and beyond the reach of most scientists. Researchers, especially archaeologists, are often on the periphery of this industry-driven world. One question at CISA3 is: how do we make things faster, lighter, cheaper and ultimately better without assuming the burden of cost? The only place this kind of innovation is going to happen is on campus because a lot of what we want and need, we either can’t afford or it simply doesn’t work for us in the field. The students themselves are filling this gap through the process of developing creative solutions. They go in consumers, and come out makers, and those skills are going to put them in a much better place.”

A number of CISA3 students, including CSE Ph.D. student Vid Petrovic, are assisting Rissolo with documentation of the underwater Mexican cave site known as Hoyo Negro, where underwater explorers discovered the remains of several species of extinct megafauna as well as a Paleoamerican girl nicknamed “Naia.” The discovery presented, for the first time, hard evidence to support the theory that Native Americans descended from Siberians who crossed into America via a land bridge over the Bering Strait. Rissolo and his colleagues published the results of their study in the journal Science last May.

Rissolo and the CISA3 students are in the midst of a digital in-depth post-expedition analysis of the site in the form of 3D models that can be studied interactively and collaboratively, as well as precise physical replicas created on CISA3's 3D printers. Rissolo is currently working with National Geographic and the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City to showcase the work.

Rissolo is also in the early stages of working with Qualcomm Institute Director Ramesh Rao to develop a campus-wide collaboration with San Diego’s Balboa Park in the hopes that UCSD student and faculty projects will be shared through the park’s museums.

“The idea is to tap into a lot of the interesting things we’re doing that have broad appeal across museum communities,” he says. “We want to play a more active role in telling stories across campus to support our campus-wide mission, not just from an engineering perspective but from the perspective of all the interesting threads that connect projects and programs at UC San Diego.”

Part of Rissolo’s job as Special Projects Coordinator will be to work closely with the students to help them identify more sources of funding and understand how the world of grant writing works, as well as to help them think strategically about how to get their research published. But what he’s most excited about, he says, is providing the CISA3 students with the types of experiences he wishes he had more of while a student: the ability to work on projects that develop real-world solutions.

“I want students to know they can do good science, even as an undergraduate,” he adds. “It’s not just about going to class and taking tests; you can be doing, making and producing. How many engineering students get to develop camera traps for wildlife or crawl around in caves in Mexico? I never knew it was possible to do this when I was in school. I thought as an undergrad you were supposed to keep your head down and grind through it.

“But the experience these students are getting at CISA3 is something they will remember forever, and it’s because we give them an experience they’re not anticipating, and that their future employers aren’t anticipating,” adds Rissolo. “Employers want someone who can understand teamwork, think on their feet, be resourceful and creative. That’s what we’re turning out. I see confidence emerge in the students who start to take charge of their academic and professional careers, and it’s our job as mentors to help nurture that.”

Related Links

Center of Interdisciplinary Science for Art, Architecture and Archaeology

Media Contacts

Tiffany Fox, (858) 246-0353, tfox@ucsd.edu