Shedding New Light on a Renaissance Master

By Doug Ramsey, dramsey@ucsd.edu, 858-822-5825

San Diego, February 10, 2009 -- Visitors to the San Diego Museum of Art can catch a glimpse of the museum of the future. There, alongside the "Madonna and Child" by early Renaissance artist Carlo Crivelli, is an LCD display playing a video that takes museum-goers beneath the surface of the painting.

|

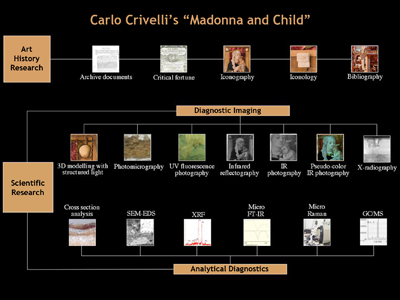

Much of the imagery came from multispectral imaging and other diagnostic tools deployed by scientists and engineers at the University of California, San Diego's Center of Interdisciplinary Science for Art, Architecture and Archaeology (CISA3). The video went on display last week to update the public on the findings of a partnership between SDMA and CISA3. Crivelli's 1470 painting is one of half a dozen Renaissance works in the museum's permanent collection that are being studied in minute detail to create prototypes for what CISA3 Director Maurizio Seracini calls "digital clinical charts" for works of art.

CISA3 is based in the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology (Calit2), and is a partnership with the Jacobs School of Engineering and UC San Diego's Division of Arts & Humanities. The video was produced by Calit2 in conjunction with SDMA. "It's a Madonna and child, the most common subject of Renaissance painting," says museum curator John Marciari.

Carlo Crivelli holds a special place in the pantheon of Renaissance artists. He sits outside the mainstream of painting's development in Renaissance Italy. Yet his creative imagination and his abilities as a painter can rank with those of any of his more famous contemporaries. His Madonna and Child is one of the treasures of the permanent collection at the San Diego Museum of Art, and a high-tech project to document the genesis and state of conservation of the work now shows that there is much, much more to the painting than meets the eye. And according to John Marciari, the museum's curator of Italian and Spanish paintings, the work can help new audiences appreciate Crivelli's eccentric but beautiful style: "He doesn't look like other Renaissance artists, he's a stranger, and this image is typical of his work. You have this rather severe sculptural virgin, and a frankly strange looking child, and this interesting give-and-take between the old mode of painting, and the new naturalism that we see develop in the years leading to 1500.

|

Crivelli left Venice for good in 1459 - first moving to Padua, where he studied the works of Francesco Squarcione and Andrea Mantegna, then to a port town on the Adriatic Sea, today called Zadar (now in Croatia, but at that time part of the Venetian Republic). Ultimately, Crivelli settled in Le Marche, first in the town of Fermo, and later alternating between Fermo and Ascoli Piceno. But he signed his works as "Carlo Crivelli from Venice" until his death.

|

Forgotten then, but no longer, thanks in part to the Digital Clinical Chart project, launched by UC San Diego's Center of Interdisciplinary Science for Art, Architecture and Archaeology - CISA3 - and its director, Maurizio Seracini. "You need to use technology, especially multispectral imaging, that can capture at different depths the visual understanding not only of the genesis but also problems of decay that are not recognized with just the naked eye," says Seracini.

Seracini is a pioneer of art diagnostics and is taking it to the next level in a partnership between CISA3 and the San Diego Museum of Art. They are prototyping the clinical chart for art works. The idea: to do for paintings what physicians do before diagnosing or treating a patient - take the patient's history, perform all necessary scans, and even do biopsies if necessary.

|

"The clinical chart has this purpose: to establish the anatomy, the pathology, and follow-up on the pathology," responds Seracini. "We are in a prototype stage, not only in how we structure it, but in the research and development of the proper technology and methodology to be used in order to create a clinical chart."

"The San Diego Museum of Art is very fortunate in that it has a great collection of Old Master paintings, and the Italian paintings are perhaps its greatest strength. We have work beginning with Giotto from the early Renaissance, all the way to the later Renaissance and singular works by Crivelli and others. The Crivelli, when John arrived here, stood out as a work that could yield a bunch of new information for us all," notes Cartwright.

|

The construction of the clinical chart begins by assembling the sort of information that museums have always assembled for their collections: scholarly literature, archival research, provenance records, and so forth. Some of this information is gathered from records and books, and some from the painting itself: a view of the back of the Crivelli panel, for example, reveals old exhibition labels as well as the red wax seal of the collector Oscar Huldschinsky, who owned the painting early in the 20th century.

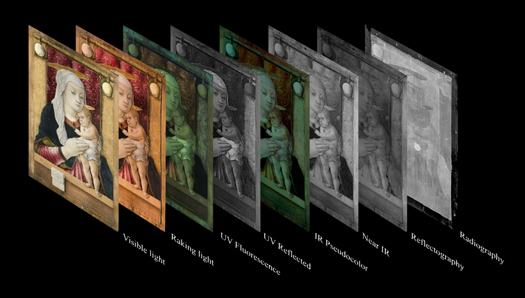

This information is then juxtaposed with scientific examinations, including very high resolution imaging, ranging from 3D laser modeling, to various types of infrared, ultraviolet, X-ray and other techniques - each of which provides unique insights into different layers of a painting. "Normally the sequence of multispectral acquisitions is to use a wavelength that will help you first establish what's on the surface and then move into the painting all the way to the support," says Seracini.

The Crivelli was first photographed in extreme detail, with cameras and filters deployed on an automated arm. Dozens of images were then stitched together, and the resulting visible-light image shows details that used to require a microscope to see. CISA3 researchers use the world's highest resolution display system, the HIPerSpace wall at the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology, to make sense of the enhanced detail. These brilliant new images help the scientists and the curators study the painting, but they can also be used to demonstrate some of its key points to the public.

|

|

For all the obsessiveness of the underdrawing, Crivelli departs from it in places. Comparing the visible-light image with the infrared, for example, you can see how he first thins, then thickens, the curve of the child's calves, trying to refine that position. The computer-generated overlays of the multispectral scanning process also allows curators, scientists - and now the public - to fade in and out, from one "layer" of the painting to another. Through this process one can easily see, for example, places where Crivelli departed from the carefully drawn pattern on the cloth behind the Madonna. But why did Crivelli do detailed underdrawings that - to Crivelli's knowledge - no one would ever see?

|

With the underdrawing complete, the gold leaf would then be applied to the painting. Special punch tools were used to create patterns in the gold. Only then would painting begin. Here too, Crivelli used an elaborate technique, working in multiple layers.

"Then we move into the range of the infrared band," explains CISA3 director Seracini. "Here we operate at 1 micron, especially in the pseudo-color infrared."

Pseudo-color infrared helps with identifying pigments, he adds: "Since most of the pigments and binding media are transparent in this wavelength range, it is possible to gather information from the infrared light sent over the painting and reflected at different depths."

Most of the painting was in tempera, which involves color suspended in protein binding media (such as egg white). "You can see the very tiny brush strokes typical of this technique, with pseudo-color infrared we were able to identify the specific colors used by the artists, for example, the red edge of the robe of the Madonna, which becomes yellow in the pseudo-color IR due to the presence of vermillion."

Crivelli's painting was made around 1470, a time when Venetian painters were beginning to use oil paint. Ultraviolet light produces a very bright, yellow fluorescence on oil paint, so scans in that spectrum make it easy to detect which parts of Crivelli's painting were done in oil, and which were done in tempera. "For as meticulous Crivelli is with little strokes of tempera paint, or his obsessive cross-hatched design underneath the tempera when he gets to oil paint., he paints in what in closeup photography look like sloppy, broad strokes. He was just at this point learning to use oil paint, the consistency of which and properties of which are radically different from tempera paint," explains SDMA's Marciari.

|

Notes Marciari: "You will see in some of the images of the X-rays and infrared photography how differently the oil is handled from the tempera paint."

The ultraviolet scans are also an essential tool in documenting what has happened to the painting since Crivelli painted it. The greenish glow over the surface indicates more than one layer of varnish. "Then we see restorations, some of which look dark, because they have absorbed the UV light. That is usually indicative of recent restorations, and we don't mean only cleaning or overcleaning, but in the case of the Crivelli, I should say re-painting," says the CISA3 director..

Seracini points to thin lines of repainting to fill in some of the major craquelure lines, as well as black spots, indicative of over-painting.

"Then we move to the X-ray, which is much more penetrating obviously," adds Seracini. "It is a projection of the radiopacity of different materials, in this case the panel."

Previous attempts to fill holes in the wood panel with gesso appear clearly as bright, white dots on the X-ray. Explains Marciari: "We know there was some event which caused a major cracking of the paint surface that is visible to the naked eye, but especially in microscopic photographs. This is probably the moment when the panel warped and when it lost its original frame."

Also visible: the extent to which wood worms have eaten into or out of the panel. But the study of wood worm holes can also confirm that the painting was not part of a larger work. "If you trim a panel, you expose trails, the size of trails, whereas the worms only ever go directly in or out. So as long as the holes are nice clean round entry holes, you know you have the original edges," says Marciari.

In time, pigments fade, varnishes darken, and wood panels warp - all of which generally leads conservation work. Today conservation work is done in pigments that can easily be removed, but in the past, much more aggressive means were used in attempts to freshen up old paintings.

"One oddity from the X-ray is a series of incisions carved into the painting's surface, but they seem to have been made not before it was done, as you'd often find, but long after the painting had already cracked. So it may have been by a restorer who may have cut these incisions to give the contours more relief or more depth," explains SDMA curator John Marciari. "We also see three or four earlier campaigns of restoration work on the panel that date, possibly one from the 16th century, and there are at least two or three more in the 19th and 20th centuries - the sort of thing you'd find on any Renaissance painting. Certain pigments were harmed by cleaning solvents, especially the green and the brown shadows of the child's legs that are very much damaged and slightly remade, and the blue of the virgin's robe seems to have been completely repainted at some point, but perhaps early in its history."

At some point long ago, the painting lost its original frame, which was nailed directly onto the surface of the panel, in the now-unpainted margin. The frame moldings were usually also covered in gold leaf, but in this case, the researchers found traces of red paint all around the margin of the painting, and determined that at least the inner edge of the frame was vermillion red. This is unusual, but just another of the many facets of the painting that the recent research has revealed.

Still ahead for the project are a series of diagnostic tests that will hopefully provide answers to some of the questions raised by the multispectral imaging. "We still have not done pigment analysis or cross-section analysis. There are some places were we are curious about the layers of paint, and which are original and which are retouching, and when that retouching may have been done," says Marciari. "If there is any significant time lapse, in a cross-section looked at sideways, you'd see a layer of dirt just from the dust in the studio."

Says SDMA executive director Cartwright: "It's again this marriage of John's expertise with Maurizio's, which brought the Crivelli forward as an object that was ripe for this kind of study, because John knew from his experience looking at other works by Crivelli that there would be very interesting underdrawings that were not necessarily part of past studies of this painting. Indeed, that's what we found out, that that's the case, and there is a lot of material there not visible to the naked eye, which with Maurizio's tools and the insights of the Calit2 scientists were able to bring that out to show it to the public in a very compelling way."

"It will allow us to call up the infrared image, or X-ray and visible spectrum, and to manipulate them to study the painting and to store new images for comparison in the clinical chart. And ultimately this will be linked not only to our own database but to those of other museums that have such charts," notes Marciari. "For example, in the case of the Crivelli, it would be very interesting to know when he starts to use oil paint. And that work just hasn't been done."

Meanwhile, Marciari and the team from UC San Diego are developing clinical charts for several other key works from the San Diego Museum of Art's collection. Like Crivelli, Cosme Tura is known to have made complete underdrawings for his paintings, so Tura's "St. George" was an obvious candidate for multispectral imaging. Also included: a work by Giorgione, the masterpiece of the museum's Renaissance collection. And because Giorgione and Vicenzo Catena shared a studio, the project is developing a chart for Catena's "Holy Family with Saint Anne". "Some works kind of at the margins of Giorgione - some disputed attributions by Giorgione - might turn out to have been made by Catena, and we hope that information gathered here and compared with those in other museums' paintings may help clarify the work of the two artists," says Marciari.

All of the paintings hang in a new permanent exhibit space at SDMA for Renaissance Italian paintings. "San Diego has an astonishingly good collection of Renaissance art and I don't think most people in San Diego know that," says curator Marciari. "So by concentrating it here and having important works at the center of each wall, the Crivelli, the Giotto, the Giorgione on the opposite wall, I am hoping to emphasize the strength of this collection in this area, just as the next room emphasizes our strengths in Spanish painting."

Researchers are also scanning the Crivelli to produce a 3d mathematical model of the painting, and the model will become the basic reference onto which multispectral scans are draped to provide future curators and museum goers with virtual reality versions of the "Madonna and Child". Also ahead for the project, researchers will do point-by-point, non-invasive identification of inorganic materials, using both X-ray fluorescence, and Raman spectroscopy. And they'll use a new imaging technology that has not yet been used on paintings. It's called terahertz time domain spectroscopy:

"It is a new revolutionary technology that will be able to create an image at the interface of each layer of paint to make a spectroscopy analysis to determine which binding media is present. This will give an outstanding, incredible support to the restorer," explains Seracini.

Currently, only the wealthiest museums can afford to own equipment of the sort used by CISA3 to develop digital clinical charts. But as Seracini and his colleagues prototype a standard methodology and portable technologies - like the automated x-y-z scanner already developed at UC San Diego - Seracini says the cost of the equipment will come down: "As in any new science, we have to see that this is the prototype, the early stage. But I truly believe that any museum out there will be able to afford it."

According to Derrick Cartwright, the executive director of SDMA, "The clinical chart, well applied, will be a standard reference for these objects in the future, and if we can develop a useful model that can be exported to other institutions, I think you'll find that a lot of museums will be able to use these techniques to help them in their conservation efforts."

Concludes CISA3's Seracini: "I can see how museums can finally join together in tackling these crucial problems related to conservation and also dissemination of new understanding of these works of art beneficial for the public at large."

Seracini and his colleagues in CISA3 hope their work at the San Diego Museum of Art will lead to a worldwide cyberinfrastructure, accessible via the Internet, to allow museums and researchers to upload and share their clinical charts - one day paving the way for new collaborations, new findings, and a more scientific way of monitoring and safeguarding the health and safety of great works of art.

Media Contacts

Doug Ramsey, 858-822-5825, dramsey@ucsd.edu

Related Links

San Diego Museum of Art

CISA3