Integrating Medical Science with IT for Emergency Response

9.19.02 - The first anniversary of September 11 has just passed, but fear remains about the potential for similar catastrophes in the future. Everyone can remember from personal history -- or imagine from Hollywood's relentless need to situate an empathetic hero in danger for 90 minutes -- what it's like to experience a toxic plume from an industrial accident, the lurching feeling of an earthquake, or the acrid stench of a neighborhood on fire.

9.19.02 - The first anniversary of September 11 has just passed, but fear remains about the potential for similar catastrophes in the future. Everyone can remember from personal history -- or imagine from Hollywood's relentless need to situate an empathetic hero in danger for 90 minutes -- what it's like to experience a toxic plume from an industrial accident, the lurching feeling of an earthquake, or the acrid stench of a neighborhood on fire.

Now all the public discussion about weapons of mass destruction brings to mind even worse possibilities -- a terrorist nuclear or chemical attack, and then the question: What help can I count on if something very big and nasty happens where I am, especially if thousands of other people are affected?

After a year spent mourning September 11, most of us now follow that question with one that's higher on the empathy scale: What happens to those kind souls, the first responders, who, as they are trying to help us, endanger themselves?

Unfortunately, such attacks have already taken place. On March 20, 1995, between five and six thousand Tokyo-jin were exposed to the nerve gas sarin by a domestic terrorist organization Aum Shin Rikyo.![]() Amazingly, only 12 died -- nine in the subways, one at the hospital, and two a few weeks later -- though, sadly, 3,794 were injured, and many still suffer from brain damage.

Amazingly, only 12 died -- nine in the subways, one at the hospital, and two a few weeks later -- though, sadly, 3,794 were injured, and many still suffer from brain damage.

The first responders went to the sites without any protective gear or plan, and 135 were also exposed, mainly ambulance drivers wheeling away people whose clothes were lightly saturated with the clingy sarin organophosphate molecules. Few of the hospitals had any information on sarin. "Fewer than 50 per cent of the hospitals sought information on sarin poisoning from the Japan Poison Information Centre (JPIC). The Center's telephone lines were constantly blocked for many hours after the accident."![]()

And yet only nine months before, Aum Shin Rikyo had exposed 300 people to sarin, killing seven in Matsumoto, only two hours by train from Tokyo. Fire fighters and medical workers were also exposed in this incident. And it was Matsumoto's doctors who, on March 20, faxed instructions on sarin treatment almost at random to colleagues at various hospitals in Tokyo, enabling reduction of the proportionate exposure-to-killed ratio from 1 in 43 to 1 in 500, an order of magnitude improvement with 127 lives saved via a few-thousand-yen worth of fax cost.

The lessons of the March 20 incident are that coordination, both within individual agencies and across agencies, must be defined, developed, debugged, and deployed ahead of time.

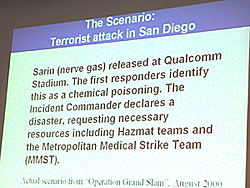

A slide on Operation Grand Slam, which simulated a sarin chemical weapons attack to help train emergency medical responders in San Diego. |

These lessons have been taken to heart in San Diego County where emergency responders at 20 agencies work together in a Metropolitan Medical Response System

Team,![]() one of the first MMRS teams in the country, with 200 cities establishing them as part of homeland security preparations. The MMRS conducts full-scale exercises, such as "Grand Slam Thursday" on August 24, 2000, which simulated a sarin chemical weapons attack at QUALCOMM Stadium, a bigger version of the March 20 event.

one of the first MMRS teams in the country, with 200 cities establishing them as part of homeland security preparations. The MMRS conducts full-scale exercises, such as "Grand Slam Thursday" on August 24, 2000, which simulated a sarin chemical weapons attack at QUALCOMM Stadium, a bigger version of the March 20 event.

In this context of new urgency, professors and doctors at UCSD are engaging in iscussions with local emergency medical response teams as part of a larger UCSD/SDSU regional homeland security study. Calit² researchers are teaming their expertise in medicine, communications, geolocation, and computing to advance the state of the art in emergency medical response.

Out of this has grown a systems integration project called WIISARD - Wireless Internet Information System for Medical Response in Disasters - which leverages the ongoing work of three Calit² living labs: Ubiquitous Connectivity, SensorNets, and Knowledge and Data Systems.

WIISARD aims to prototype and test technology and methodology that could be deployed when large numbers of people at a major event, such as at a football stadium, are attacked with chemical or conventional weapons. It would be just as useful for more frequent crises induced by nature or industrial accidents. Such scenarios are characterized by uncertainty about the cause and impact, and the potential for victims to flee, unintentionally contaminating others, including emergency responders.

Dr. Leslie Lenert |

The WIISARD team is directed by Dr. Leslie Lenert, an M.D. in the UCSD School of Medicine and Chief of the Laboratory for the Study of Patients' Preferences, a joint activity between UCSD and the Veterans' Administration Hospital.

Lenert's education and training could serve as an archetype for a new era of health care specialists. Lenert looms large at Calit² not only because he's a fit six-foot-five but because he integrates two disciplinary fields with different vocabularies and communities well enough to serve as a human Rosetta Stone.

Equally fluent in the specialized languages of medicine and information technology, Lenert graduated with a combined B.S. and M.D. in a UCLA/UC Riverside program where he specialized in internal medicine and pharmacology. He was also one the first to earn an M.S. in Medical Information Sciences at Stanford (now called Biomedical Informatics) where he studied everything from genomic analysis to determining what makes patients happy or enables them to live longer.

Lenert says, "The classic focus in medicine has been on diagnosis. That's good for a start, but it's not sufficient. I've always been very interested in therapeutic design making, so I like to ask: What are the risks, and how do we balance them?" Lenert goes on to explain, for example, that drugs used to prevent toxicities from nerve gas agents are toxic themselves.

Some research suggests that such agents might be a cause of Gulf War Syndrome. "How do we determine when a drug offers more benefit than risk?" summarizes Lenert.

WIISARD seeks to save lives by integrating Lenert's focus on rapid and prioritized action into a family of procedures to locate people, triage them into categories of injury severity using active tags and bar codes, quarantine those affected, provide appropriate treatment based on urgency, and direct the first responders to where they can do the most good. The result, according to Lenert, who wrestled with the depressing problem of trying to quantify the lives that could be saved using different approaches, will be to save lives in general.

Says Lenert, "Let's say there is a chemical weapons attack on a stadium with 70,000 people, and there are 1,000 seriously wounded. By implementing WIISARD, we think we could probably save 150 who would otherwise die."

Lenert adds that the acronym for the project is rather appropriate. "We are providing a 'wisard's shield' of the medical infrastructure to mitigate the damage," he says.

Lenert's expertise in computer science, quite uncommon for medical doctors, enables him to leverage Calit² research activities in the Ubiquitous Connectivity living lab. "At the VA Hospital, we were fascinated by the potential to use computers and communications to accelerate delivery of sound medical care. We'd been trying to get collaborations going for a year, but it took the dynamic force of Larry Smarr and Calit² to get things moving."

Lenert points to an editorial Smarr published on the application of information technology and telecommunications to manage disaster response in the San Diego Daily Transcript last October as a general architecture that WIISARD customizes to emergency medical response.

Smarr, director of Calit² and co-Principal Investigator on WIISARD says, "The Calit² homeland security work adapts technologies we are working on for civilian applications and re-integrates and customizes them to address the needs of homeland security."

All the technologies that Lenert is adapting to WIISARD have been prototyped previously on other Calit² projects, specifically wireless Internet, location-aware devices, bandwidth management for best connection, and data visualization. For example, Lenert's working with

-

Sujit Dey, UCSD Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE), on sensor networks for the human body to record vital measurements and provide real-time updates on medical status.

-

Ramesh Rao, Calit² UCSD division director and a professor in ECE, integrating CDMA2000, Bluetooth, and 802.11b wireless communications more seamlessly.

-

Chaitan Baru, San Diego Supercomputer Center, on creation of incident databases, and robust data management and query processing techniques in the presence of missing data due to possible, periodic network disconnections.

-

Sid Karin and Mike Bailey, SDSC, on data security and data visualization, respectively.

In addition, a number of Calit² industrial partners are involved, from large companies like QUALCOMM to startups like PhiloMetron.

Lenert considers it vital that the systematic integration of these technologies and data become integral to emergency response to help doctors frame the response, even before first responders arrive at the incident site: "All resources of the hospital -- medical records, infrastructure, monitoring -- need to be available wirelessly in the field where medical care is being administered, while patient data, from the time they receive their tags to the time they get to the hospital, needs to be transmitted so hospital personnel can be waiting with the right expertise and equipment for them, all ready to go."

Dr. Leslie Lenert spoke at the UCSD Homeland Security Workshop, held on August 22, 2002. |

WIISARD is advancing the infrastructure for taking measurements and acting upon them. Says Lenert, "It's extremely important to have multiple pulse oximeters, for instance, because the injured might have low oxygen or abnormally high or low pulse. If both of these indicators are abnormal, the patient is likely to be in critical condition."

Lenert, mindful of the cross-contamination of the care providers in Japan during both sarin attacks, is investigating the use of portable sarin detectors to determine whether victims have sarin molecules, even if in minute concentrations, in their clothes. These detectors have been prototyped by Calit² researcher Michael Sailor, UCSD Chemistry and Biochemistry, who will be the subject of a future article.

In one Calit² scenario being designed and tested, doctors will carry Pocket PCs in hospitals saturated with Wi-Fi wireless internet. Such Pocket PCs, wireless tablets, or even the new color CDMA cell phones can access local medical records, lab results, prescription drugs, real-time patient vitals, and a mincam for videoconferencing. Doctors in such 21st-century hospitals could head for an emergency site, where similar Internet access could be rapidly deployed, providing emergency medical personnel secure access to every patient record they normally would have in the hospital.

Smarr says, "We want the doctors to be able to transfer their working environment to the field. Of course, WIISARD is prototyping for future situations, not today's."

UCSD's "CyberShuttle" experiment,![]() providing such mobile Internet access (by using QUALCOMM's cellular CDMA2000 wireless as a backhaul for Wi-Fi inside the bus), has been tested recently in an ambulance scenario.

providing such mobile Internet access (by using QUALCOMM's cellular CDMA2000 wireless as a backhaul for Wi-Fi inside the bus), has been tested recently in an ambulance scenario.![]() This integration of technology can enable an emergency physician in a hospital, especially a remote one, to "look over the shoulder" of a paramedic in the ambulance, thus assuring optimum care while the patient is being transported to the hospital. Given that some patient traumas, such as stroke, require high-resolution imaging, Calit² has been working with private sector partners to enable such imaging access, a story I will return to in the future.

This integration of technology can enable an emergency physician in a hospital, especially a remote one, to "look over the shoulder" of a paramedic in the ambulance, thus assuring optimum care while the patient is being transported to the hospital. Given that some patient traumas, such as stroke, require high-resolution imaging, Calit² has been working with private sector partners to enable such imaging access, a story I will return to in the future.

The architecture of WIISARD is comprised of PDAs for first responders and smart badges for patients that can be located and tracked via Global Positioning System (and, later, possibly UItraWideBand localizers). The badges will have enough memory to store a record of treatments, observations, diagnosis, and/or prescriptions. Badges will increasingly incorporate sensors such as Sailor's sarin sensors, though these will mostly need to start on vehicle-mounted sensor platforms that can then become backpack, then badge-sized.

These sensors will likely be linked to emerging advanced 911 data systems, as will be discussed in a future article on Chaitan Baru, SDSC, who is radically rethinking how to analyze aspects of 911 calls - 60,000 such calls are received on a daily basis - such as time and location to optimize emergency response. Wearable computers, including those popularized via high-technology fashion shows produced by my company Charmed Technology, are also being evaluated and will be an integral part of future emergency response systems.

All these technologies will spawn a tsunami of data that needs to be visualized in a manner that can provide instant, easily assimilated status reports to inform decision making in remote control centers. And command centers with immersive visualization theaters are emerging to address this need.

Calit² helped prototype two at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and San Diego State University. SDSU has developed a visualization system (as described in a previous article![]() ) for oceanographic and seismic data that allows researchers to handle multi-gigabyte files with data wands in real time, moving around to see a 3-D or 4-D view of very large and complex environments, such as earthquakes or changes in oil reservoirs over time. Significantly, Calit² researchers involved in WIISARD, benefiting from proximity to apparently unrelated disciplines, have come to appreciate the potential benefit that smaller versions of this visualization theater might provide if set up in hospitals or emergency response control centers.

) for oceanographic and seismic data that allows researchers to handle multi-gigabyte files with data wands in real time, moving around to see a 3-D or 4-D view of very large and complex environments, such as earthquakes or changes in oil reservoirs over time. Significantly, Calit² researchers involved in WIISARD, benefiting from proximity to apparently unrelated disciplines, have come to appreciate the potential benefit that smaller versions of this visualization theater might provide if set up in hospitals or emergency response control centers.

And the webbing that ties the PDAs, smart badges, sensor platforms, cyber ambulances, 911 citizen-sensor nets, and command center visualization systems together to enable this enhanced care to improve outcomes will be next-generation wireless Internet, which some call "4G."

A number of tests have been designed to compare the treatment quality provided to a simulated victim with and without WIISARD protocols. "In the former," says Lenert, "emulating the system in place today, someone on the radio will be shouting, 'Help! Someone's had an accident north of the quad.' And everyone will start asking questions and guessing. In contrast, with WIISARD, the responders will get a map on their handheld computers, and they'll go right to the victim. It's all about customizing medical care and improving outcomes by making the most effective use of the first few minutes."

----------------------------------------------------------------------

1. http://www.terrorismanswers.com/groups/aumshinrikyo.html

2. http://www.sos.se/SOS/PUBL/REFERENG/9803020E.htm

3. http://www.calit2.net/research/activeCampus/1-29-02.html

Related Links

WIISARD