Bill Griswold's Adventures in Transparent Infrastructure

Professor Bill Griswold (right) shows graduate student Matt Ratto (left), and researcher David Hutches (center) how to use the ActiveCampus program. |

Though it was only on the screen for a few seconds, thousands of people found this application compelling enough to almost wish transparent aluminum into existence. Reports, and even photos, purporting to announce its imminent arrival in our day appear regularly on the Web.![]() ("Needless to say the Pentagon is quite interested.")

("Needless to say the Pentagon is quite interested.")

As powerful as that idea was, Bill Griswold, professor of Computer Science and Engineering in the Jacobs School at UCSD and the Calit² UCSD layer leader for Interfaces and Software Systems, is taking the idea of transparency one step further -through his vision of transparent infrastructure and his team's innovations in the ActiveCampus project, part of Calit²'s Ubiquitous Connectivity living laboratory.

Griswold's aim is noble: Help his community, which is growing rapidly in population, maintain the intimacy of a smaller, more tightly knit community. Griswold's community just happens to be UCSD, which, together with Calit²'s partner UCI, faces the challenge of absorbing some 35% of the anticipated growth in the UC system over the next 10 years. UCSD alone expects to grow from 20,000 to 30,000 students and by nearly 500 net new faculty. His starting point is a kind of a new-fangled wireless Welcome Wagon to help new members of the campus community come easily up to speed on who's who and what's going on.

Though meant initially for thousands of humans, the longer-term implications for humanity of this new technological approach could be profound. This is because the Earth is being transformed by the growth in its urban megacities. According to the United Nations, urbanization has been one of the most important developments of the last century, and today almost three billion people live in urban areas.

The explosion of megacities, each big enough to be seen from space at night,![]() is shocking. There were no megacities (more than 10 million people) at the turn of the century. In 1950, there was only one, New York, which had reached this milestone in 1925. In the year 2000, there were 19, and, by 2015, there are projected to be 23. Another way to look at the global newbie issue: According to the United Nations, urban populations grow by 60 million a year, with about twice this number (equivalent to the entire east coast of the U.S. from Boston to Atlanta) migrating each year.

is shocking. There were no megacities (more than 10 million people) at the turn of the century. In 1950, there was only one, New York, which had reached this milestone in 1925. In the year 2000, there were 19, and, by 2015, there are projected to be 23. Another way to look at the global newbie issue: According to the United Nations, urban populations grow by 60 million a year, with about twice this number (equivalent to the entire east coast of the U.S. from Boston to Atlanta) migrating each year.

Immigrants new to their city of choice are disoriented from leaving the family and neighborhood structure of their village or town and entering a strange environment with little ability to find out where things are or how to make friends with similar interests.

|

With the millions of migrants moving to megacities in mind, let's return to Griswold's project. The basic "business model" for ActiveCampus is simple: Give new members of a community a wirelessly and geolocated-enabled PDA![]() that will show-and-tell them where they are and what's around them (including the insides of buildings), and let them post notes about any person, place, or thing, and exchange messages with each other, in effect providing an answer to the command: "Get a clue!" The answer: "Okay. I just downloaded several."

that will show-and-tell them where they are and what's around them (including the insides of buildings), and let them post notes about any person, place, or thing, and exchange messages with each other, in effect providing an answer to the command: "Get a clue!" The answer: "Okay. I just downloaded several."

From the (unkind but universal and timeless) viewpoint of upperclassmen, there is no group more clueless than college freshmen, making the latter ideal subjects for Calit²'s ActiveCampus. Griswold and colleagues have embraced 500 Jornadas, donated by HP Compaq, and applied a medium dose of technological ingenuity and a large dose of social ingenuity.

True to the Calit²'s paradigm for a living laboratory, the subjects of the experiment, a la Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle, change the experiment almost every time they look at what Griswold gave them. "Students taught me mercilessly - I wasn't going to have icons and messaging, but students insisted on them," says Griswold. Such is the democratizing effect of new communications technology.

Not only did students insist on being able to use icons, they wanted to design their own, so a young woman with an interest in tennis could represent herself as a racquet, while a music fan could look like a CD album cover. Free speech undergoes yet another image upgrade.

Griswold is passionate about the role the university can play in developing a community of learners and points to early universities like Heidelberg in Germany as some of his archetypes. "It's folk wisdom," he says, "that most learning takes place outside the classroom. University education is a process of socialization and acquiring tools that prepare you for a life of problem solving. We want to stimulate creation of novel approaches to analyzing, evaluating, and engaging with phenomena without the arbitrary distinction of whether the activity is happening inside or outside the classroom. Learning should be able to take place anywhere."

ActiveClass, which involves the research participation of Calit²-funded undergraduate fellows, is one application Griswold has developed. Says Griswold, "Imagine that all 150 students in a class, the professor, and the TA all have either a wirelessly enabled PDA or laptop. Students, for cultural or gender issues, or fear of embarrassing themselves, may choose to submit a question only by typing it into the application. This question - boom! - pops up on everyone's screen."

Students can vote on these questions, and the most popular - highest ranked - questions guide the professor instantaneously on what is of greatest interest - or confusion - to the students. The professor, looking at a "teleprompter" displaying the rank-ordered questions of the minute, can include an answer in the next sentence, without disrupting the flow of the lecture. Also, it gives shy students a way to participate more actively in this newfangled class "discussion." Griswold likens this situation to "electronic training wheels for class participation."

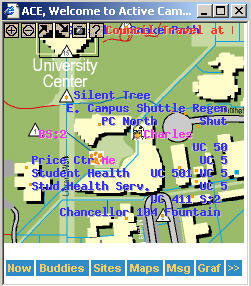

A second application, ActiveCampus Explorer, is Griswold's way of making the local infrastructure transparent. UCSD has developed this enormous infrastructure to house departments, equipment, faculty, students, and projects. But the very infrastructure that contains these elements also takes them out of view. So the question, says Griswold, is "How can we make these opportunities more visible to students, and how can we encourage students to seek out new people, places, projects, and things?"

ActiveCampus Explorer uses the metaphor of transparent infrastructure to show students what's available. ("Captain, they've taken my transparent aluminum into a whole new dimension!" exclaimed Montgomery Scott.) Imagine a student with a PDA accessing the wireless Internet. The device is capable of detecting its own location in physical space and can serve up a map of its vicinity and, overlaid on that map, entities that are in that physical space. It can show colleagues nearby, restaurants, art work, and whatever else you might imagine. The location is found in Griswold's experiment by triangulation from the Wi-Fi access antennas, but

Calit² is experimenting with other geo-location technologies such as cellular techniques, GPS, and MEMS gyroscopes, all of which I will return to in future articles.

|

Also overlaid is a marker indicating the device's location in the sense of "You are here." It's very easy - through a quick visual inference - to see what's nearby and for the user to click on an icon, see the Web page, and determine whether a visit is warranted.

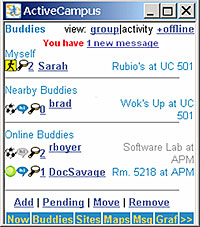

Griswold's group has come up with a software system for communicating between "geo-buddies," an enhancement of the core concept of ICQ ("I seek you," Yosi Vardi's innovation that claims 120 million users who automatically present their friends or "buddies" with an tiny icon in a desktop window showing when they are online.![]() And, if you didn't already know that, you need to stay in more!

And, if you didn't already know that, you need to stay in more!

Using the geo-buddies functionality, students can choose to let their friends add them to a "geo-buddy" list on their PDAs, and their spatial position will be shown as an icon on the buddies' PDA. That way, friends can find one another when they are on the campus. This is the beginning of a profound overlap of the cyber and physical world-think of it as IM![]() -augmented reality!

-augmented reality!![]()

Griswold, like all good computer scientists, takes the twin issues and tradeoffs - privacy and security - very seriously. In addition to the software protections in the system, users can add, delete, or become invisible or accessible, at the touch of an icon and a button, to preempt the possibility of stalking (though a stalker would have to be a bit daft to do this, since his or her actions, for the first time, could be proven by looking at the logs of icon location queries and location updates). Thus, privacy and security are, paradoxically, enhanced by having more location information, providing fertile new material for future researchers, very likely including the pioneering student users of the system.

UCI professor and science fiction author Gregory Benford sees this and other computer networks as a sort of "arms race," in which some people try to apply technology and ingenuity to get around the system, while others, seeing these attempts or actions, take corrective action. In the process, rapid enhancements, improvements, and learning curve effects occur, until, after a few years, the system is robust enough to become a standard not just for other UC campuses, but, hopefully, for the rest of the world.

|

After their use and fine tuning through the 2001/2002 academic year in which they were a novelty, the ActiveCampus PDAs have become the stars of a new show, featured during the first orientation - called "Explorientation" - of the UCSD undergraduate Sixth College. Sixth, in late September, opened its doors to 285 freshmen who were quite possibly the least "clueless" in history. Gabriele Wienhausen, Provost of Sixth College, is the Calit² UCSD layer leader for Education and an enthusiastic collaborator with Bill Griswold.

In classic Calit² fashion, Griswold went outside his department (Computer Science and Engineering) to find a fellow Calit² researcher to help create novel content to stretch the capabilities of the devices. Adriene Jenik, associate professor of Visual Arts at UCSD and member of the Calit² New Media Arts layer, describes her specialty as "developing theatrical interventions into Internet visual chat rooms to engage deeper public debate about the rapid adoption of life-shaping technologies." This startling statement seems fitting when you experience her Explorientation challenges or game play, a "crash course" in cooperative PDA use.

"Maprobatics - one of the six 'challenges' of Explorientation," she says, "stimulates the students to use creative spatialization, messaging, and cooperation to arrange themselves into a visually compelling display." Students can submit custom icons for further aesthetic impact.

"It's a modern 'take' on getting students to be able to act like a marching band, seen from the air - only more creative," she says. Trigger, Tag, and Tell got students running to different objects placed around campus and being the first to "tag" the site with a message.

After the orientation, one can imagine these students will start coming up with activities that no one, including Griswold and Jenik, has thought of. Already students are posting digital notes to the Chancellor's residence ("Tuition is 2 high," which elicits the reply, "It's already 80% subsidized by CA state - stop yer whining!").

So, is ActiveCampus just fun, games, and a new way to get a date - or something more? Anyone with even a passing knowledge of America's historical development and recent economic boom can imagine that ActiveCampus could have revolutionary consequences. Unlike almost any other country, America's cities were started by boosters who acted on their best behavior to attract newcomers and make them feel informed and valued participants.![]()

In the time since these incoming freshmen were born, the booms in desktop publishing, computer gaming (think Core wars and Zorn), early Internet content (USENET), the World-Wide Web, Wi-Fi broadband wireless, i-Mode, and SMS (short messaging) were all started by innovators and early adopters who happened to be college students having fun and playing around.

In the end, the history of human progress comes down to better ways to live, work, and play together, from hunter-gatherers to Starbucks Wi-Fi Web surfers. And ActiveCampus, by inviting from Day 1 the participation and codevelopment by its users, sets a new standard for fulfilling the potential of the university, so named because it's meant to encompass all knowledge and make it accessible to all present.

ActiveCampus gives Cal (IT)², other researchers, and students/users an unprecedented opportunity to compare and contrast today's experiences with a future that holds forth the amazing possibilities of geolocation and ubiquitous Internet connectivity. Because every student and professor is provided with a device, we can more easily imagine, for the first time, what will happen when mass marketing (rather than much appreciated corporate and government grants) make these devices available to affluent consumers and, 20 minutes into the future, as affordable as a pair of new sneakers. Indeed, much of the functionality of ActiveCampus is becoming available in third-generation cell phones with geolocation and messaging built in.

Following the cost curve of Moore's Law, what costs $500 today will be $50 "tomorrow" and $5 a few "tomorrows" after that. The Bangladesh Grameen Bank model has already put tens of thousands of mobile phones in the hands of villagers who share the costs. In the next decade, we may see an "ActiveCity" application on next-generation personal devices that could point out where food, water, firewood, jobs, and, better yet, wheat prices were, potentially improving the quality of life for all concerned.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

1. http://www.rense.com/general20/transparentalum.htm. Note that transparent aluminum does not yet exist, but people hoped it did, in one case spamming the Web and even Slashdotting a Der Spiegel story until it was corrected.

2. You must see and zoom around on this nearly real-time image as an example of "transparent civilization," then forward it on to friends! http://www.fourmilab.ch/cgi-bin/uncgi/Earth/action?opt=-p

3.Personal Digital Assistant, a handheld computer with a screen and either a tiny keyboard or a pen for scripted input, typically using the Palm, Epoc, or Pocket PC operating system.

4. http://www.icq.com offers more information and downloads. Try it out, as this is the #1 way young students keep in touch before they get mobile phones and will give a glimpse into the future of communications (very near term, as in Max Headroom's 20 minutes into the future.)

5. Instant Messaging

6. Augmented reality, along with wireless television, will be the two biggest brand new booms in the Internet in this decade. AR involves overlaying text, data, or images of variable transparency onto the real world, usually triggered by something in addition to the user, such as location, proximity, or context. See University of Washington Human Interface Technology lab,http://www.hitl.washington.edu/, or my book, Brave New Unwired World (John Wiley, 2002), for more information.

7. According to historian Daniel Boorstin in The Americans: The National Experience, American town creators were historically unique in setting aside land and taxes to build colleges and universities, even when there were just a few houses, because they wanted the new blood and flood of ideas and innovation that universities were known to attract.