Washington Post Calls Calit2’s Smarr ‘Unlikely Hero’ of Global Movement

San Diego, May 10, 2015— Calit2 Director Larry Smarr made the front page of The Washington Post. The May 9 article, “The Human Upgrade: The Revolution Will Be Digitized” by technology writer Ariana Cha, explores the movement to quantify consumers’ health and lifestyles, spearheaded by a flood of wearable devices such as the FitBit and Apple Watch. The article calls Smarr “the unlikely hero of a global movement among ordinary people to ‘quantify’ themselves” using an estimated 211 million wearable monitoring devices to track their own health statistics (68 million devices shipped this year alone) – and using the knowledge to approach their physicians in new ways.

“From the instant he wakes up each morning, through his workday and into the night, the essence of Larry Smarr is captured by a series of numbers: a resting heart rate of 40 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 130/70, a stress level of 2 percent, 191 pounds, 8,000 steps taken, 15 floors climbed, 8 hours of sleep,” is how Cha opens her feature article, adding: “Smarr, an astrophysicist and computer scientist, could be the world’s most self-measured man. For nearly 15 years, the professor at the University of California at San Diego has been obsessed with what he describes as the most complicated subject he has ever experimented on: his own body.”

As described in the article, Smarr monitors more than 150 parameters related to his health and activity. Some parameters are continuous (e.g., whether he’s standing, sitting or lying down, as well as his heartbeat). Other factors are tabulated on a daily basis, such as his weight. Then less often, he has his blood and the bacteria in his intestines analyzed. As he has often done in the past, Smarr compared his self-monitoring with the way many Americans monitor their own cars. “We know exactly how much gas we have, the engine temperature, how fast we are going,” he is quoted as saying. “What I’m doing is creating a dashboard for my body.”

And Larry Smarr is not alone, reports Cha. “The explosion in extreme tracking is part of a digital revolution in health care led by the tech visionaries who created Apple, Google, Microsoft and Sun Microsystems,” she wrote. “Using the chips, database and algorithms that powered the information revolution of the past few decades, these new billionaires now are attempting to rebuild, regenerate and reprogram the human body.”

She quotes Sun co-founder and investor Vinod Khosla as saying that thanks to more sophisticated wearables, “we can begin to cross-correlate and understand how each aspect of our life consciously and unconsciously impacts one another.”

The article signals the next generation of health tracking devices which could be as small as a grain of sand – nano-sized particles that can travel in the bloodstream and attach to diseased cells. The particles could be monitored by a wearable device, which could transmit the data to the patient or physician. As wearables increasingly become ingestibles, Cha reports that the “innovation is outpacing the scientific and legal framework for testing and regulating such devices.” She noted that the FDA earlier this year indicated it would regulate devices that are invasive, “but take a lighter touch on wearables.” In the absence of regulation by the FDA, the current generation of wearable trackers are being monitored by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (e.g., when the CPSC worked with Fitbit on a recall of more than one millon devices in 2014).

Returning to Larry Smarr’s journey to self-monitoring and improved health, the Washington Post article notes that it began when he moved to California in 2000 to join the UC San Diego department of Computer Science and Engineering, and to lead Calit2 (“the West Coast equivalent of MIT’s famous Media Lab”), which “aims to rapidly develop prototypes of technological innovations and test them in the real world.”

Writer Ariana Cha sees Smarr as taking Calit2’s multidisciplinary philosophy and applying it to “investigating himself.” “Although he had no previous experience in medicine, nutrition or biochemistry, he trained himself, he said, by reading more than 600 journal articles on monitoring and health,” the writer reports.

“We are in a once-a-century period of discovery about the human organism,” Smarr is quoted as saying. “The mythology in this country is you can do whatever you want to your body, and a doctor will give you a pill to fix it. That needs to change.”

The article notes that “an increasing body of behavioral medical research has found that patients who track their diet, physical activity and weight achieve better results than those who don’t, suggesting that wearable monitors provide feedback that reinforces personal accountability.”

For Smarr, self monitoring helped him reach a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory bowel disease, and he continues to pay special attention to his microbiome. “You are an ecology, and the health of those bugs determine how you are,” Smarr told the Washington Post.

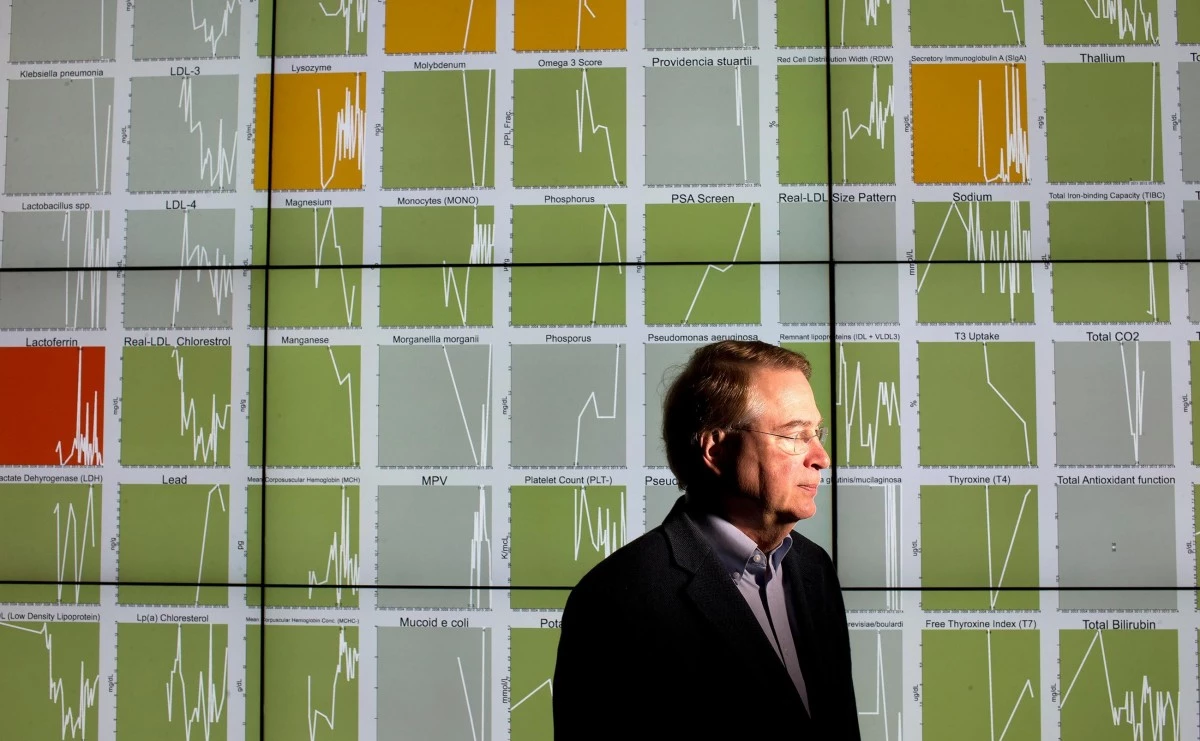

The article includes a photograph of Smarr dwarfed by the Vroom display system in the Calit2 Theater, which displayed “150 key variables about his body over a 10-year period, displayed in colored rectangles. Most were green, meaning they fall within the expected, health range. But some were yellow (one to 10 times outside the healthy range) and a handful were red (10 to 100 times outside the health range).”

The Future Patient project led by Smarr produced a variety of tools for tracking his incoming data, and some of that data recently showed that his body remained in “attack mode”, and he’s still not sure why. As he admitted to the reporter, “people overestimate what knowledge can do for you.”

The Washington Post article includes a number of interactive features. One is a quiz, which purports to let consumers know which type of fitness tracker they are – The Hypochondriac, the Slacker Tracker, the Competitive Tracker, etc. Another feature is a game designed by the Post, giving the reader seven promising tools for prolonging how long we live (beyond the 80-year average for the average American. The game asks, “Can you make it to 100 years or beyond?” The tools to prolong life include reprogramming cells, neural stem-cell transplants, rejuvenated blood, spray-on skin, bioprinted organs, custom-built bones, and anti-aging pills.

Media Contacts

Doug Ramsey, (858) 822-5825, dramsey@ucsd.edu

Related Links