Capturing Public Support For An Endangered Species Through A Photograph

By David Wang

San Diego, February 26, 2016 — Just four hours south of the University of California, San Diego campus lives the most endangered marine mammal in the world: the vaquita porpoise. Despite the Mexican government’s ban on gillnet fishing in the northern Gulf of California, fishermen on the hunt for totoaba fish and shrimp continue to use the nets illegally, leading to the incidental capture of vaquita, which become tangled in the nets and drown. According to the World Wildlife Fund, the estimated 100 individuals remaining are at risk of becoming extinct by 2018 if accidental capture is not prevented immediately.

The importance of these small cetaceans can not be overemphasized. According to the San Diego Zoo Institute For Conservation Research: “The vaquita is an apex predator surviving on smaller, more abundant marine creatures, keeping their populations in check and the ecosystem in balance”.

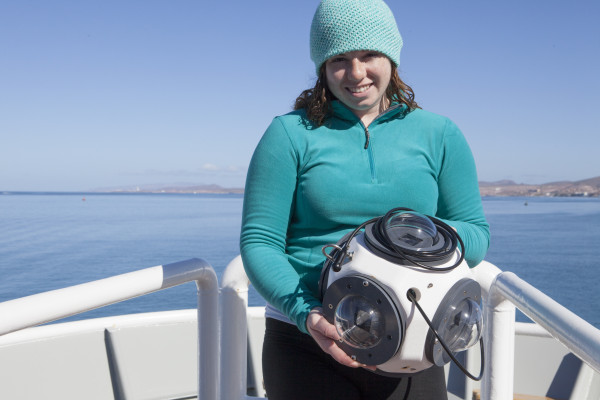

With aspirations of a thriving vaquita population in mind, UC San Diego Ph.D. student Antonella Wilby of the Kastner Research Group holds the newly developed underwater camera, the Spherecam, in hand to accelerate conservation efforts. The Spherecam, which was developed by Wilby and others in the Qualcomm Institute-based Engineers for Exploration (E4E) program, contains six cameras orientated on the faces of a cube, which provide a 360°x360° view of the surrounding environment.

Wilby, who is affiliated with E4E, hopes to capture the first image of a live vaquita in its natural habitat. The Vaquita Monitoring project received noticeable attention earlier this year from National Geographic, which is funding Wilby’s project through a Young Explorers Grant. National Geographic published a blog post by Wilby, which highlighted her innovative technological approach of using vaquita acoustic vocalizations to trigger the Spherecam camera. As a follow-up to that article, we sat down for a Q&A session with Wilby about her quest to creatively raise awareness of this issue.

Q: Photos of the harbor porpoise have already been captured along the coastal waters of the Northern Hemisphere. What makes the vaquita porpoise particularly difficult to trace? How have these factors been considered in designing your research strategy?

Wilby: Vaquita is by nature a very shy porpoise, which makes it difficult to observe. They tend to stay far away from boats and swim away from the sound of boat motors. My collaborators have observed that they typically stay around 800 meters to a kilometer away from their research boats, when they are sighted. This behavior isn’t restricted to just vaquita — for example, Burmeister’s porpoise is similarly shy and rarely photographed in the wild, even though the population of Burmeister’s is probably a lot bigger than the vaquita population.

Additionally, even though their range is tiny compared to the range of other marine mammals, the fact that there are so few members of the species remaining makes it that much harder to find them in the wild. They don’t exhibit any jumping behaviors like some species of dolphins, which would make them easier to spot. They tend to surface to breathe quietly and quickly before disappearing again, so the seas have to be very calm in order to spot them. There have been many days when we’ve been in the field and the water has been too rough to even go out on the small fishing boat we work on, much less have a good chance of sighting a vaquita. It’s a combination of factors that makes them so rarely spotted.

The fact that they’re so scarce and difficult to observe was the main motivator in the design of our remotely-triggered monitoring system. It’s not feasible to have a human with a camera in the water long-term, so we decided to take a different approach. Since the system is triggered off of their vocalizations, it can be left unattended in the water in locations where vaquita are frequently detected by the existing hydrophone monitoring system. I anticipate that the system will need to be in place for awhile before the strategy is effective, since even though we can detect vocalizations from far away, the animals will not always come within range of the cameras.

Q: You mention that you haven’t been successful in capturing a photo of the vaquita. Have any clicks been recorded by the acoustically-triggered camera system so far? If so, how have you been distinguishing between dolphins and porpoises?

Wilby: Up until now, I’ve been focusing on engineering and testing the different systems in the SphereCam. It hasn’t detected any clicks yet, but this month it will be starting its first long-term deployment in the field, so hopefully we’ll get some detections soon.

Dolphins can vocalize in a much wider frequency range than porpoises. The echolocation clicks of porpoises are in narrow-band, high-frequency bursts, whereas dolphin clicks cover a wider frequency range. Vaquita’s particular click has a peak energy at 139kHz and ranges from around 122 to 146 kHz, so we’re using an ultrasonic transducer that is sensitive in that band and looking for signals at 139kHz.

Q: Your passion for undersea adventure is transparent in your Nat Geo article: “I was fortunate to snorkel amongst tropical fishes at Punta Colorado, observe a sea lion hunt and devour a yellowtail snapper at Los Islotes, and come within feet of a ‘small’ whale shark in La Paz while learning shark facts from Dr. Hammerhead.” Can you explain how your interest in exploration ties into your research?

Wilby: Exploration and a love of nature have always been a fundamental part of my mindset. I didn’t grow up as a “tech kid” with computers being a part of daily life. I spent most of my time outdoors, playing in the yard or on camping trips. But when I discovered the world of robotics and research, I realized that the mindset of an explorer and the mindset of a researcher are no different. Both are focused on discovery and fueled by an insatiable drive to push the limits of human knowledge.

When I came to UC San Diego and got involved in Engineers for Exploration and the Kastner Research Group, I learned that there are countless ways that technology and robotics can be directly applied to exploration. There’s so much we don’t know about the world, and so much left to be explored. My primary goal is to solve problems in the field of robotics and apply that to exploring the ocean and the rest of the world. I’ll be very excited if one day my job title is “Exploration Roboticist.”

Q: It’s clear from your Nat Geo article that you have a hunger for new knowledge: “I learned about the unique ecosystems in Baja California (did you know there’s a rattlesnake without a rattle?”). What is one question you hope to answer upon capturing a photograph of a live vaquita in its habitat?

Wilby: There are so many questions that we can answer by getting visual data on the species. Getting one photo will be great for media purposes, but ultimately if we’re able to capture many photos of different individuals we will learn a lot about the species. For example, scientists are able to identify individual blue whales by the shapes of their dorsal fins and the pigmentation on their flanks. As far as I know, we have no way to identify and track individual vaquitas. Maybe with “eyes in the water,” we will be able to identify individuals based on characteristic markings that we can’t see from far away, and track them over time if they are captured on camera multiple times. We might be able to guess the age of individuals, or get an estimate on how many mothers and calves there are in the population. We might learn more about social behaviors, or breeding patterns.

As an engineer, I would like to provide the biologists who have studied this species for years with innovative ways to get new information. Much of engineering is focused on building stuff for people, but I think there is a great need for building tools to further all fields of science. There is not as big of a market for these things so it’s not as lucrative, but I believe that engineering should go hand-in-hand with foundational science to further discovery.

Q: You mention the highlight of your time aboard the National Geographic Sea Bird with the Committee for Research and Exploration (CRE) was discussing the goal of “educating the public about the importance of protecting the natural world.” And while it may take some time to capture a photograph, is there anything the general public can do to help prevent vaquita extinction?

Wilby: In my opinion, the most important thing people can do is get educated on these conservation issues and tell the story to others. It’s a compelling issue, and I think the main thing preventing people from getting passionate about it is that they don’t know it’s happening. In San Diego, we’re four hours away from the center of this major conservation issue — you can almost take a day trip to see where it’s all happening (though it’s unlikely you’ll see a vaquita, unfortunately).

Once people have heard about the problem, they can start making personal choices that will have an impact. For example, a lot of shrimp you can buy in the USA is fished using gillnets from that area. If there is demand in restaurants and stores for vaquita-safe shrimp, that economic pressure will filter down to the fishermen, who will have a lot more incentive to use the new vaquita-safe fishing gear since people will not want to buy their catch otherwise.

Also, the VIVA Vaquita Coalition has put together a petition to make the gillnet ban in the Gulf of California permanent. You can add your name to the petition to show support for vaquita conservation, and share the petition so that more people can learn about this critical issue.

______________

Antonella will continue writing stories from the field for National Geographic Voices and updating followers about engineering-specific developments on the Engineers for Exploration blog.

Media Contacts

Tiffany Fox

(858) 246-0353

tfox@ucsd.edu