UC San Diego Cyber-Archaeologist Participates in ‘Dialogue of Civilizations'

University of California San Diego anthropology professor Thomas E. Levy is back in San Diego after participating in the fourth International Conference on Dialogue of Civilizations, held in Ahmedabad, India and co-organized by the National Geographic Society, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) and India’s Ministry of Culture.

Begun in 2013, the conference series was created to encourage scholarly discourse about five ancient, literate civilizations of the world: Egypt; Mesopotamia; South Asia; China: and Mesoamerica. Previous Dialogues took place in Guatemala (2013), Turkey (2014) and China (2015). The series is the brainchild of Christopher Thornton, PhD, Senior Director of Grants & Human Journey of the National Geographic Society.

The Oct. 8-15 conference began with a gala opening in Delhi at the Ashok Hotel. The academic deliberations were hosted by the Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar (IITGn) near Ahmedabad in Gujarat state where international National Geographic explorers presented on the early civilizations of China, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Meso-America. Indian researchers focused primarily on new scholarship and insights into the Harappan Civilization, particularly in the state of Gujarat, which has excavated Harappan settlements from all three phases of the civilization dating as far back as 360-2600 BC (pre-urban), 2600-1900 BC (urban), and the late Harappan period between 1900-1300 BC. At IITGn, the delegates were treated to a ‘Dance of the Civilizations’ by students from a local Gujarati high school that was right out of Bollywood with wonderful choreography.

During two full days of academic sessions, Indian speakers focused on what is known about Harappan craft production, technologies, trade and communication – with particular focus on planning, water and hydrology in the ancient civilization.

UC San Diego’s Levy participated on a panel on “how new technologies provide insights into ancient civilizations.” His presentation focused on “Cyber and Marine Archaeology: New Technologies for Investigating Coastal Civilizations.” Levy is the director of the Qualcomm Institute-based Center for Cyber-Archaeology and Sustainability (CCAS) and co-director of the new Scripps Center for Marine Archaeology (SCMA), a partnership between the Department of Anthropology and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

“As we move further into the 21st century, some of the most meaningful ‘dialogues of civilization’ are taking place in coastal areas around the world, where land and sea environments meet and the full expression of human adaptation and cultural evolution takes place,” said Levy. “To adequately record, curate and disseminate the archaeological data from sensitive coastal zones to answer historical and anthropological questions, the technologies of digital and marine archaeology need to be combined.” Levy and his team are doing just that, with an initial study focusing on the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1200 BC) collapse of the Mycenaean, Hittite and New Kingdom Egypt civilizations in the eastern Mediterranean region, from Greece in the west to Israel in the east, with particular interest in the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1200 BC) collapse of civilizations. By studying climate, environmental, and cultural change in this period, Levy added, “it is possible to understand some of the new opportunities that arose in the subsequent Iron Age (ca. 1200 – 500 BC) as a result of the power vacuum that occurred with the demise of these civilizations.”

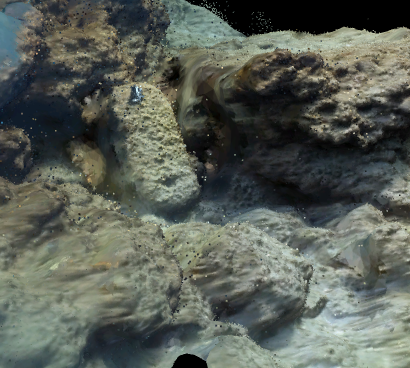

Levy also called on archaeologists of ancient civilizations to adopt an integrated approach to dealing with the essential processes linked with field science: data acquisition, curation, analysis, and dissemination. He highlighted recent research linking land and sea archaeological investigations through the lens of cyber-archaeology, including experiments with underwater structure-from-motion (SfM) photography of a submerged Iron Age port on the coast of Israel, and the use of airborne SfM drone photography to capture and create 3D models of ancient coastal sites.

Others on the opening panel with Levy included Francisco Estrada-Belli from Tulane University working on extensive aerial LiDAR surveys of the Maya region, Yukinori Kawae of Nagoya University (Japan) who presented on 3D modeling of Old Kingdom pyramids in Egypt, and Chase Harrison and Sarah Parcak (University of Alabama) on crowd-sourcing and remote sensing in Egypt and Peru. A subsequent panel on “Craft Production and Technologies” featured talks by Renee Friedman (Oxford University), Aslihan Yener (Koc University, Turkey), Barbara Helwing (University of Sydney), and Li Liu (Stanford University). A third panel covered “New Insights to the Harappan Civilization”, with talks by India’s K. Krishnan and Sanjay Kumar Manjul, as well as China’s Xinwei Li Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing). Overviews of the earliest civilizations were presented by Augusta McMahon (Cambridge University) on Mesopotamia and Anna Latifa Mourad (Austrian Academy of Sciences) concerning Second Intermediate period Egypt, and

In addition to UC San Diego’s Levy, U.S. delegates to the conference included National Geographic lead program officer Christopher Thornton and Monica L. Smith, an anthropologist who holds the Doshi Chair in Indian Studies in UCLA’s Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. Prof. Smith will co-edit the conference proceedings with Dr. S.B. Ota, Joint Director General, Archaeological Survey of India. Anabel Ford from UC Santa Barbara presented on Mayan hydraulic strategies.

Another speaker, University of Baroda Prof. P. Ajithprasad, argued that the Dholavira site in Kutch added new dimensions to Harappan Civilization, including the use of millets in agriculture, exploitation of marine gastrobod shells and semi-precious stones for craft production, the introduction of drill bits for stone bead manufacturing, production of textiles using cotton, jute and wool, and more. Other speakers pointed to discoveries that show just how advanced the Harappan Civilization was. For example, archaeologists have found what they consider the earliest ploughed field (at Kalibangan in Rajasthan); evidence of the earliest datable earthquake (also in Kalibangan); and the world’s earliest dockyard (found in Gujarat).

Indian Minister of State for Culture, Dr. Mahesh Sharma, opened the meeting in Delhi, noting that settled human life in the Indian subcontinent goes back to around the 9th millennium BC during the Neolithic Period, eventually leading to the Harappan Civilization, which was largely lost to history until the first Harappan sites were excavated in 1921. Today there are roughly 2,500 Harappan sites known on the Indian sub-continent.

Click here to watch short video clip of two dances.

“It is rewarding to know that the chronology of this civilization was already dated” to the 3rd millennium BC, Dr. Sharma noted in his inaugural address. “Written records were absent and this was before the availability of radiocarbon dating method, but early trade between the Harappans and the Mesopotamia Civilization made it clear how early the Harappans were active in the region.” Soon after British archaeologist Sir John Marshall announced the discovery of the Harappan Civilization, scholars working in Mesopotamia began noticing discoveries of Harappan objects in modern-day Iraq and Iran. Radiocarbon dating later pinpointed the flourishing of the civilization to circa 2600-1900 BC.

Other Indian scholars at the conference, including distinguished Prof. B.B. Lal (age 95) – who spoke to the attendees in New Delhi at the gala, contributed other perspectives on Harappan Civilization, including its history of discovery and invention. A past recipient of India’s prestigious Padma Bhushan Award, Dr. Lal noted that Harappan Civilization was the earliest known on the subcontinent, and he highlighted advances in town planning, agricultural and animal husbandry, arts and crafts, trade, and political structures.

At the conclusion of the conference’s academic sessions, Prof. Levy and other attendees took an eight hour bus ride to one of the most extensive archaeological sites of the Harappan Civilization’s urban period: the fortified city at Dholavira in the district of Kutch in the state of Gujarat.

Dr. R.S. Bisht, former Joint Director General of the ASI and excavator of Dholavira, gave the delegates a personal tour of the site. The site features a substantial water conservation and management system. Inhabitants of Dholavira created a series of reservoirs and channels to conserve water, including at least nine reservoirs of varying sizes cut out of bedrock and built up with elaborate stone masonry. The system provided fresh water to the flourishing Harappan city – and archaeologists say the water system represents the high-water mark of Harappan technology, which was critical to the civilization in the already-arid Kutch region (which today gets very little rainfall all year round). The delegates camped out for two nights at Dholavira in beautifully appointed tents that are part of an eco-tourism project to promote tourism to this remote area. Each night, delegates were treated to Gujarati folk dance performances. During the day, there was a demonstration by traditional craftsmen who specialize in making beads using methods that can be traced back to the Harappan period.

A large number of antiquities were unearthed at the site, including seals as well as beads of semi-precious stones made of gold, silver, copper, and shells, as well as terracotta figurines. Excavations have also turned up antiquities of west Asian origin – remnants of Harappan trade with Mesopotamia.

The final conference in the National Geographic-initiated Dialogue of Civilizations is planned to take place in Egypt, but no date has been set.

Media Contacts

Doug Ramsey, 619-379-2912, dramsey@ucsd.edu